Balfron Tower (pic: @balfronsocial)

If only Balfron Tower could talk, if only we could see

A Balfron Social Club guest blog post by Stephen Pritchard

Time lapses. Remembrances. Lives once fixed, now in transit. Different places. Other spaces.

If only Balfron Tower could talk.

Each wall, window, walkway. Every conduit, fixture, fitting, lock. The underground garages. The lifts. The noticeboards. Dispossessed.

The views. People’s views. Displaced.

If only we could see.

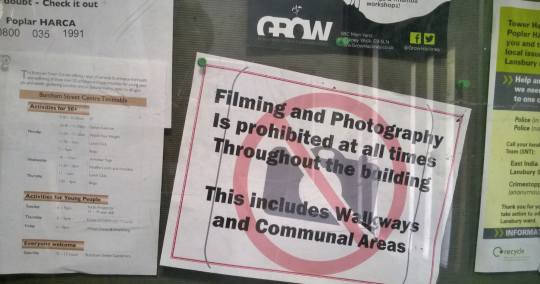

No filming. No photography.

Fixed perspectives. Fixed outlooks.

No filming, no photography (pic: @etiennelefleur)

All the while, the City creeps nearer. Beacons. Warning signs. Shiny neoliberal lights. Precursors of forthcoming “redevelopment”. Glass fronted. Flimsy giants. Harbingers of impending gentrification. They are coming. They will come. They will erase generations, feast on the past, wipe clean past lives, past happiness, past hardships. Brutal.

Call in the artists, the property guardians, dark soundtracks, bleak CGI mock ups trumpeting “We’re coming home, baby!”

Not yet. Just Sitex doors. Left possessions tipped in skips. Locks. For now.

Business suits, fluorescent-clad workers, white-shirted private security guards. Builders or destroyers?

A Sitex door bars access to the former home of an elderly Balfron Tower leaseholder, bullied from his home through the courts with threats of a Compulsory Purchase Order (pic: @balfronsocial)

Balfron Tower was a refuge for its many social housing tenants. Soon it will be another vacuous space filled with neoliberal lifestyle choice, as empty of lives, real lives, as the empty promises made by the local “housing regeneration and community association” and the luxury residential property developers. A haven for thieving City bankers. Left-empty overseas billionaire investments. Hedge fund safe bets. Tax evasion. Buy-to-leave.

And now the last resident has gone, decanted to God knows where, they have wiped the soul from Balfron Tower. It will never return. They will make sure of it. They have replaced people with assets for private investors, homes with a “new world” bereft of communities – another dead world of capital investment. A global world of shadowy deals and care-free exploitation. Their world.

Cinema. Launderette. Play Room. Garden Room. Cocktail bar. Goldfinger Archive. Trunk Store. Treehouse. What? Social housing transformed into 1960s “design icon”, how lovely. How incredibly ironic. How to “unlock the potential for an unprecedented cast of stakeholders”.

So wrong. So, so wrong.

Up for the Yoga Room, down for the Music Room, design proposals for the Balfron Tower regeneration (Source: unknown)

And yet, Balfron Tower remembers its proud past. Its residents will never forget. Their ups and downs are cast in screed. Their births and deaths, breakups and marriages haunt stairwells and walkways. Lifts murmur songs from decades of everyday living. Everyday hymns to everyone and no one.

Balfron Tower, like its past residents, remembers. Together, they remember things heard and overheard; seen, unseen and overseen; touched and untouched. Spoken, now muted, conversations. Different people, living together high above London, through good and bad. Sharing. Learning from one another. Partying. Playing. Fighting. Living. Always living.

Inversion / Reflection shares little bits of some of these stories. Resident’s lives. Balfron Tower’s life. The film is not a crass product of socially engaged artists in the pay of profiteering property developers or housing associations hell bent on gentrification by a wryly smiling social art practice that paints a thinly disguised veil over gentrification. It stands sensitive. Understated. Peaceful. Honest. Proud. A fitting commemoration of those displaced at the hands of unbridled gentrifiers who will, with their own rabid teeth, devour themselves eventually. Cindy. Gavin. Felicity. Shiraz. Evelyn.

Inversion/Reflection: What Does Balfron Tower Mean to You? A short film by Rab Harling

Balfron Tower.

It didn’t have to be this way. Those involved didn’t need to exploit people. They didn’t have to lie. They didn’t have to socially cleanse.

This is not what Goldfinger planned.

He turns in his grave as capitalist greed stamps out the dying embers of our hopes and dreams for social housing. Balfron Tower was and still is a symbol of our welfare state. Built on optimism. Killed by selfishness. Justice for all replaced by the dog-eat-dog world of possessive hyper-individualism and neoliberal capital accumulation by dispossession. Systematic asset-stripping and land grabbing.

Balfron Tower is another battleground in a class struggle – a class war. The rich elite may have temporarily taken control but one day we will assert our right to the city and we will take it back!

A Balfron Social Club guest blog post by Stephen Pritchard

http://colouringinculture.org/

Balfron Social Club

Poplar