Homelessness charity The Big Issue gives working-class communities in London’s east end a slap in the face, as it rewards Katharine Hibbert & Dot Dot Dot for helping property developers to dismantle social housing.

From the Telegraph 3rd March 2015:

Homelessness charity The Big Issue gives working-class communities in London’s east end a slap in the face, as it rewards Katharine Hibbert & Dot Dot Dot for helping property developers to dismantle social housing.

From the Telegraph 3rd March 2015:

It is beyond question that Doreen Fletcher is a talented painter, and her paintings display a nostalgic sentimentality for a rapidly changing east London, an east London whose communities have faced a turbulent time over the past 20 years, as the east end is changed beyond recognition.

Fletcher has been adopted by the East London Group, which promote the works of painters such as Albert Turpin and Harold Steggles, “mostly working class, realist painters whose formal education had often stopped at elementary school”, they portrayed a grimy smoke-filled vision of the east end. Doreen has been promoted as a “lost artist”, an artist previously ignored by the art establishment, whose work is now being brought to the attention of the public by Paul Godfrey, aka The Gentle Author. Godfrey has published the monograph Doreen Fletcher: Paintings under his own Spitalfields Life publishing house. The book is published to accompany her exhibition with Bow Arts at The Nunnery.

Doreen’s paintings at best visually fit the canon, and at worst are derivative of the East London Group, who primarily worked in the first half of the 20th century. At the same time as the East London Group were painting the streets of east London, a wider revolution was happening in British society. In Poplar, a rates rebellion had led George Lansbury, a Labour Councillor that fought and was jailed for fighting for the rights of the working classes in his community, to become MP for Bow and Bromley and Chairman of the Labour Party. The horror that had been the 1st World War led to a boom in the building of social housing for working class communities, and the fallout from the 2nd World War led to the creation of the welfare state; free medical coverage, free education and most importantly, a safety net for those who fell through the cracks.

However, in post-Thatcher austerity Britain, a neoliberal agenda is being pursued by everybody from government, education to the arts. In the current turbulent political climate, comfort can be found in a romantic painting of an east end long since vanished, and Doreen provides plenty of comfort for us to reminisce over the past.

Godfrey’s claims that Fletcher is a lost artist however are all part of a smokescreen, an illusion that preaches community and integrity and celebrates the working class artisan, whilst imposing its singular view upon us; that of white, middle-class gentrification.

Fletcher’s CV reveals she is far from that of a lost artist, with paintings held in the collections of many civic and financial institutions. The lost artist claim serves to build up Fletcher’s mythology; to sell books, to sell paintings, but even more sinister: to sell the east end to an affluent class of investor, for them to romanticise its history; nostalgia for displaced communities that they themselves are replacing.

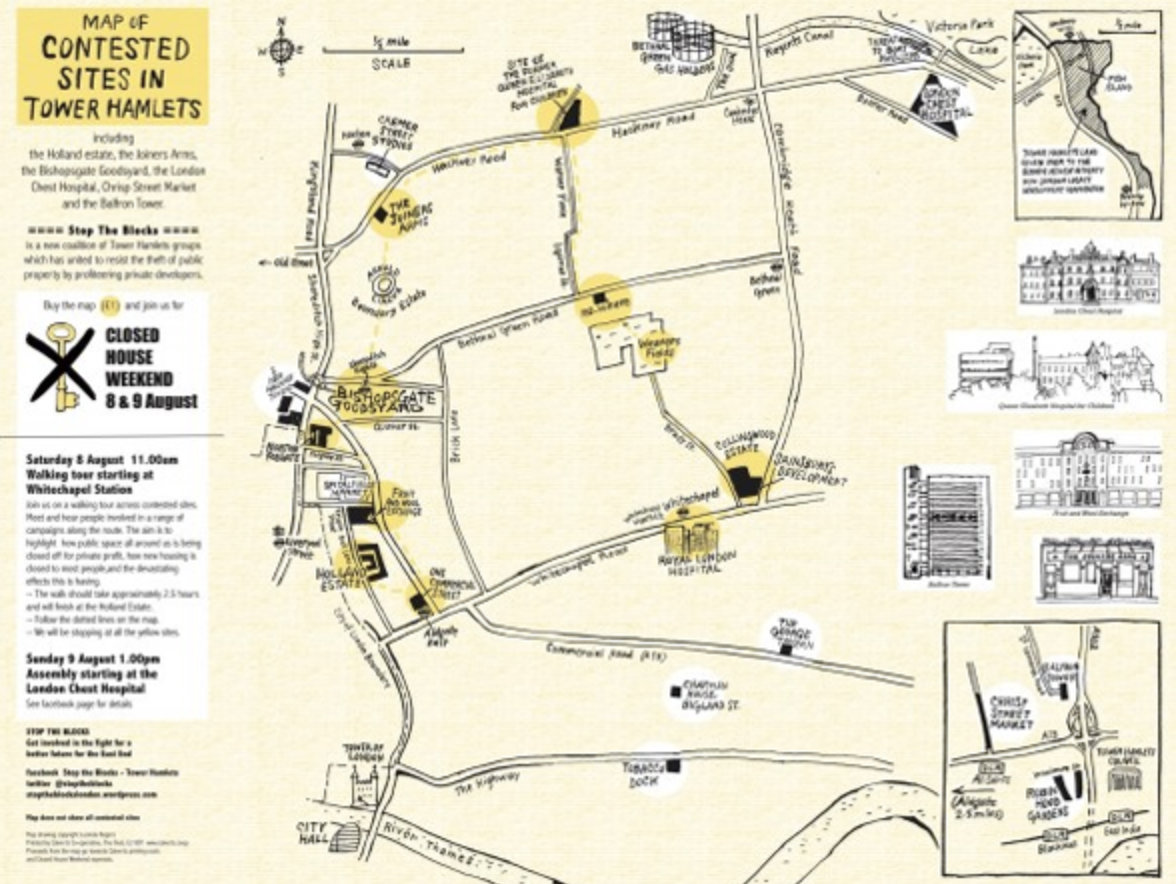

Paul Godfrey, aka the Gentle Author, first came to my attention in 2015 over his involvement in the Stop the Blocks movement. Stop the Blocks first appeared in June 2015 and disappeared just a few months later. Stop the Blocks campaigned to “save Shoreditch from the shadows” and a well attended rally was held and glossy leaflets and a large poster were produced. The poster featured local activist campaigns, including Balfron Social Club and Save Chrisp Street, accompanied by hand drawn pictures of the territory we were fighting for, including Balfron Tower.

Godfrey wrote about Balfron Tower:

Built as council housing, designed by Erno Goldfinger in 1963 and made a Grade II listed building in 1996, Balfron Tower is now being sold off by Poplar Housing & Regeneration Association. Current long-term residents are being forced to sell and moved out while the famous block is being fetishised in a sixties-style marketing campaign to attract private owners. The circumstances at Balfron Tower are a prime example of how social restructuring is devastating London’s working-class communities. Another layer of social division was added when artists renting emptied properties were co-opted tacitly into PR for the sell-off – a process that has become known as ‘art wash.’

And he wrote about the campaign to Save Chrisp Street Market:

‘Save Chrisp St Market’ is campaigning to inform local residents and traders about the proposed ‘regeneration’ of Chrisp St Market by Poplar Housing & Regeneration Association (HARCA). The plans include ‘luxury’ housing and stores, at the expense of shops and accommodation affordable for local people. Traders will be booted out for the period of redevelopment, or longer – if they cannot afford the increased rents. Traders say they have been left in the dark about the future of the market. Save Chrisp St intends to do their own consultation in parallel with Poplar HARCA’s, by going door-to-door asking people about what they would like to see for the area. So far, many people have said they want the market to be improved, but not at the cost of their ability to live there. Save Chrisp St are working to make sure that the community has a proper voice.

Despite involvement in two of the campaigns featured, no contact was ever received from Godfrey, or any of his associates before publishing the Stop the Blocks campaign poster. Stop the Blocks claimed to be a “network of grassroots Tower Hamlets campaigns fighting gentrification and social cleansing,” but seemed to be co-opting other groups, many grateful for the exposure for their campaign, for their own short-lived cause. So, it later came as no surprise to discover Godfrey had joined forces with Bow Arts.

Bow Arts had been at the forefront of the recent trend of using artists to help property developers displace communities. Their poorly managed occupation of a number of estates managed by the housing association Poplar Harca had imposed arts-led gentrification across a number of sites in the process of being socially cleansed in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

The use of artists as the foot soldiers of gentrification had various levels of success, depending upon who you asked. The Bow Arts Balfron Tower Case Study, which was no doubt lapped up without question by housing association Peabody when choosing Bow Arts to help artwash their social cleansing program in the London suburb of Thamesmead, told of a fantasy that existed inside the head of Bow Arts CEO Marcel Baettig, a fantasy where artists benefitted from targeted harassment, monitoring of their social media accounts and happily donated their landlord, a registered charity, thousands of pounds a year as a donation, taken illegally from their rent.

Bow Arts purpose was clear: it was, and remains, a publicly-funded charity who supply artists to property developers to help artwash the social cleansing and the dismantlement of social housing. Their involvement in the artwash and social cleansing of the infamous Balfron Tower serves to remind us of the direction being taken by Arts Council England, to take the lottery receipts from the Heritage Lottery ticket customers, and use it to artwash the dismantlement of our social assets.

So, is Fletcher innocent for turning a blind-eye to how Bow Arts operate? I certainly made Fletcher aware of how Bow Arts operate many months ago, but like so many artists, she chose to ignore the behaviour of who she is working with, giving them her endorsement, as well as the endorsement of the East London Group. Godfrey’s prior co-optation of sites of contestation in the east end, such as Balfron Tower suggest he was already fully aware of Bow Arts controversial role in the artwash of the east end, but chose to collaborate with them regardless. No support was ever received by Godfrey in our campaigns to save Balfron Tower or Chrisp Street Market from gentrification.

It disheartens me that artists allow their art to be deployed as a weapon against society, artwashing the reputation of some thoroughly greedy individuals and organisations, and there is no doubt that this is what Fletcher’s retrospective at Bow Arts does. Fletcher’s baby-boomer narcissism may allow her to ignore, support or collaborate in the social cleansing of the communities that she painted, but the rest of the East London Group, now deceased, have now had her ethics imposed upon them. This association with Bow Arts damages the legacy of the East London Group of painters; painters unable to object.

Balfron Social Club

Poplar, 25th January 2019

Notes:

Doreen Fletchers website https://www.doreenfletcherartist.com/

East London Group on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_London_Group

George Lansbury and the Poplar rates rebellion on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poplar_Rates_Rebellion

Closed House Weekend by Stop the Blocks in Design Exchange Magazine http://www.demagazine.co.uk/architecture/closed-house-weekend-spitalfields-life

Balfron Tower: the Artwash of an Icon by Rab Harling in Urban Transcripts Journal http://journal.urbantranscripts.org/article/balfron-tower-artwash-icon-rab-harling/

Artist squares up to Regulator over “manifestly unreasonable” fundraising investigation by Christy Romer https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/exclusive-artist-squares-regulator-over-manifestly-unreasonable-fundraising-investigation