Homelessness charity The Big Issue gives working-class communities in London’s east end a slap in the face, as it rewards Katharine Hibbert & Dot Dot Dot for helping property developers to dismantle social housing.

From the Telegraph 3rd March 2015:

Homelessness charity The Big Issue gives working-class communities in London’s east end a slap in the face, as it rewards Katharine Hibbert & Dot Dot Dot for helping property developers to dismantle social housing.

From the Telegraph 3rd March 2015:

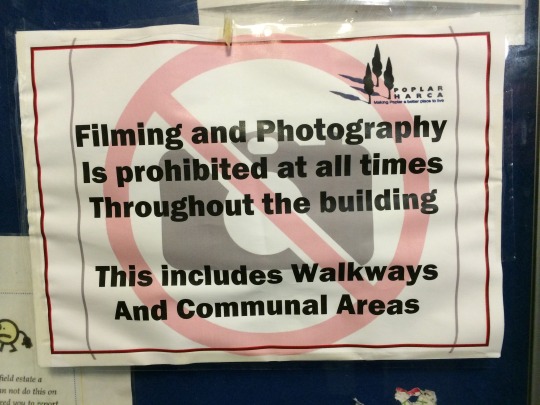

Paul Augarde, London Film School graduate and Director of Placemaking for Poplar Harca, asks residents for a chance to sort out the annexation of Poplar’s lock-up garages.

Ok, Paul. How long do you need?

Um, yeah. Cheers Paul. Well done. Have another promotion, mate.

Want to read more about Paul Augarde, Poplar Harca and how they deviate public funds towards a property developers agenda?

https://balfronsocialclub.org/2018/04/16/artwash-and-the-rhizome-the-social-cleansing-of/

As its five month installation in Living with Buildings at the Wellcome Collection draws to a close on 3rd March 2019, Inversion/Reflection: What Does Balfron Tower Mean to You?, a short film by Rab Harling, is now available to watch, free of charge, here on the Balfron Social Club website.

If you are able to visit Living with Buildings at the Wellcome Collection in central London, we highly recommend a visit to the free exhibition.

Please note that this film is displayed here for personal viewing only. Commercial or educational screening of this film is unauthorised without prior consent. Please use the Contact button for all enquiries.

Find out more about Living with Buildings on the Wellcome Collection website.

Balfron Social Club is regularly asked for help by researchers, journalists and students, so we have compiled a list of useful links and resources, for your easy reference.

This list will be updated regularly. If you have a suggestion, or have written something you would like us to include, please get in touch. This guide does not include work on the Balfron Social Club blog, so don’t forget to look at all the great content on our blog too.

Last updated 14th March 2019.

Balfron Tower: a Building Archive by David Roberts http://www.balfrontower.org/

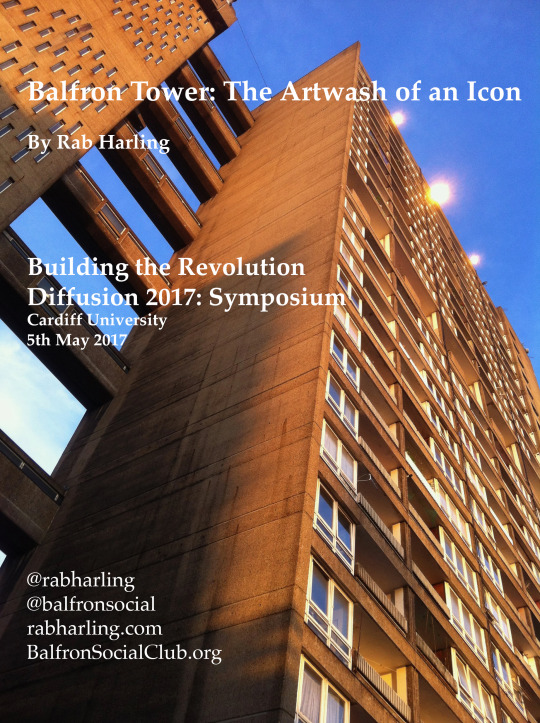

Balfron Tower: the Artwash of an Icon by Rab Harling http://journal.urbantranscripts.org/article/balfron-tower-artwash-icon-rab-harling/

Rethinking the role of artists in urban regeneration contexts by Stephen Pritchard http://colouringinculture.org/blog/rethinkingartistsinurbanregen

Wayne Hemingway’s ‘pop-up’ plan sounds the death knell for the legendary Balfron Tower by Ollie Wainwright https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/architecture-design-blog/2014/sep/26/wayne-hemingways-pop-up-plan-sounds-the-death-knell-for-the-legendary-balfron-tower

What Does Balfron Tower Mean to You? By Rab Harling http://rabharling.com/what-does-balfron-tower-mean-to-you/

C20 Society’s fears are confirmed as the Balfron Tower’s new look is unveiled https://c20society.org.uk/news/c20-societys-fears-are-confirmed-as-the-balfron-towers-new-look-is-unveiled/

Hey Creatives, Stop Fetishising Estates by Caroline Christie https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/jm953d/balfron-tower-art-fetishising-estates-157

How the Balfron Tower tenants were ‘decanted’ and lost their homes by Benjamin Mortimer http://www.eastendreview.co.uk/2015/03/24/balfron-tower-poplar-harca/

Balfron residents: ‘Privatising the tower will segregate the community’ by Dr Vanessa Crawford https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/balfron-residents-privatising-the-tower-will-segregate-the-community/8691394.article

How ‘placemaking’ is tearing apart social housing communities by Nye Jones https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/27/london-placemaking-social-housing-communities-tenants

A delicate sense of terror by Rab Harling http://journal.urbantranscripts.org/article/second-post/

Artist squares up to Regulator over “manifestly unreasonable” fundraising investigation by Christy Romer https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/exclusive-artist-squares-regulator-over-manifestly-unreasonable-fundraising-investigation

Regulator resolute on decision to side with charity over artist by Christy Romer https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/regulator-resolute-decision-side-charity-over-artist

Letter: We’re not here to defend the public – Gerald Oppenheim, CEO of the Fundraising Regulator https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/letter/letter-were-not-here-defend-public

Poplar parade of garages to become £4m East End fashion hub by Jonathon Prynn https://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/poplar-parade-of-garages-to-become-4m-east-end-fashion-hub-a3164031.html

Campaigners challenge housing association’s social cleansing policy by Tower Hamlets Renters https://towerhamletsrenters.wordpress.com/2015/02/17/561/

From sink to swank — In defence of Britain’s brutal estates by Edwin Heathcote https://www.ft.com/content/7ae5d134-bacf-11e5-bf7e-8a339b6f2164

Balfron Tower: Gutted east London fortress is a husk of a utopia by Jessica Mairs https://www.iconeye.com/opinion/icon-of-the-month/item/13178-balfron-tower-erno-goldfinger

Where do Zupagrafika stand on brutal capitalism destroying London communities by Pippa Henslowe https://reclaimec1.wordpress.com/2018/03/01/where-do-zupagrafika-stand-on-brutal-capitalism-destroying-london-communities/

Bazaar Politics: Uncovering Social Cleansing In the Heart of London by Dilly Hussain https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/bazaar-politics-uncovering-social-cleansing-heart-london/

The Pernicious Realities of ‘Artwashing’ by Feargus O’Sullivan https://www.citylab.com/equity/2014/06/the-pernicious-realities-of-artwashing/373289/

Artists Against Artwashing: Anti-Gentrification & the Intangible Rise of the Social Capital Artist by Stephen Pritchard http://colouringinculture.org/blog/artistsagainstartwashing

Campaigners and local residents are furious with a Labour council for ‘allowing social and ethnic cleansing’ by Nye Jones https://www.thecanary.co/trending/2018/07/25/campaigners-and-local-residents-are-furious-with-a-labour-council-for-allowing-social-and-ethnic-cleansing/

East End tenants ‘booted out’ of Goldfinger’s iconic Balfron Tower’ claim by Mike Brooke https://www.eastlondonadvertiser.co.uk/news/east-end-tenants-booted-out-of-goldfinger-s-iconic-balfron-tower-claim-1-3961574

‘Artwashing’ Teviot Tales – artwashing? by Hannah Nicklin http://poplarpeople.co.uk/artwashing

Labour peer Lord Cashman discusses Poplar Harca and the social cleansing of Balfron Tower in the House of Lords https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/667e22e7-c184-4d12-a33a-07a0e9737a07?in=15:50:50

A new documentary shows the harsh realities of regeneration in East London by Nye Jones https://www.thecanary.co/reviews/2018/06/17/a-new-documentary-shows-the-harsh-realities-of-regeneration-in-east-london/

Challenging the artwashing of social cleansing means calling out & critiquing artists involved by Stephen Pritchard http://colouringinculture.org/blog/callingoutartwashingartists

Interview: Bow Arts In Balfron Tower by Londonist https://londonist.com/2009/03/interview_bow_arts_in_balfron_tower

STOP PRIVATISATION AND SOCIAL CLEANSING AT BALFRON TOWER: Change.org petition by Balfron Social Club & others. https://www.change.org/p/stephen-halsey-steve-stride-john-biggs-stop-privatisation-and-social-cleansing-at-balfron-tower

RAB HARLING INTERVIEW: Diffusion Photography Festival 2017 https://2017.diffusionfestival.org/live/rab-harling-interview

Balfron Tower Redevelopment Video by Poplar Harca https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c2hVJ0_SxtI&t=2s

Balfron Tower: Not for the likes of us by James Walsh https://morningstaronline.co.uk/a-2a72-balfron-tower-not-for-the-likes-of-us-1

Mr Goldfinger’s Tower by Steve White & the Protest Family https://stevewhiteandtheprotestfamily.bandcamp.com/track/mr-goldfingers-tower

Property chiefs caught up in Presidents Club scandal by Colin Marrs https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/property-chiefs-caught-up-in-presidents-club-scandal/10027474.article

Interview: Bow Arts In Balfron Tower by Londonist https://londonist.com/2009/03/interview_bow_arts_in_balfron_tower

Property developers Londonewcastle’s marketing website for Balfron Tower http://balfrontower.com/#

Balfron Tower Redevelopment Video (July 2014) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A3FMGeJ9g6Q

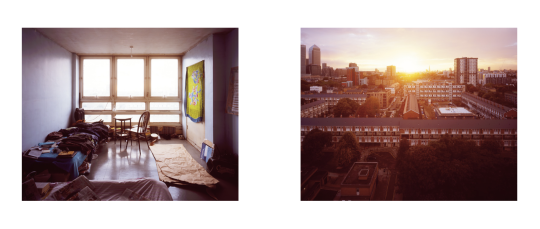

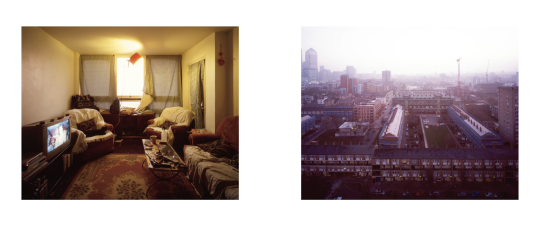

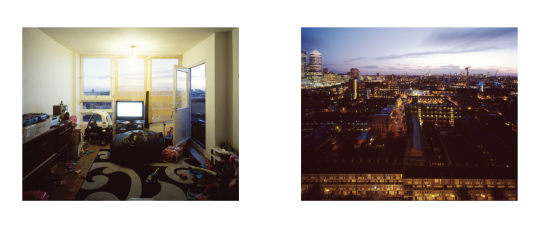

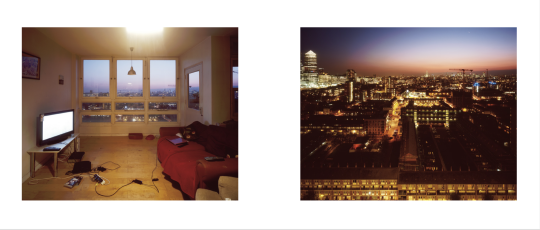

Social Housing, Social Cleansing: Balfron Tower excerpt, co-produced by Rab Harling, includes photographic and video work from the Inversion / Reflection series, and includes a personal appearance.

This excerpt taken from Channel 5’s Social Housing Social Cleansing. Directed by Paul Sng for Velvet Joy Productions. First broadcast 28th March 2018.

Balfron Tower excerpt originally featured in the cinema documentary feature film Dispossession: the Great Social Housing Swindle (2017), directed by Paul Sng. First screened at the East End Film Festival, 8th June 2017.

To watch Social Housing, Social Cleansing online: visit My5.tv

For more information on Dispossession: the Great Social Housing Swindle: Click here

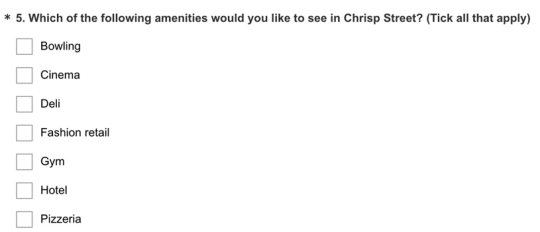

A public market serving the daily needs of the local working class community has existed in Poplar at Chrisp Street since Victorian times. In 1951, the market underwent a significant redesign by modernist architect Sir Frederick Gibberd, in celebration of the Festival of Britain, creating the UK’s first pedestrianised shopping centre.

After years of managed decline, regeneration is looming for Chrisp Street Market. A Registered Social Landlord, a property developer, and a Labour authority seek to create their vision of “the New Shoreditch”, with a brief to “change the social mix” of this 9-acre site, situated in the shadow of Canary Wharf, no matter the cost to the established community.

A mass home building program is underway in east London and new homes are rapidly being built on the graveyard of social housing, with regeneration proposals aiming to serve incoming middle class residents. Yet social housing is desperately needed by the local working class community; the people who live & work in Poplar now, rather than the people developers want to attract here.

Chrisp Street Market serves long established and diverse communities which come together 6 days a week in the market square. It serves the everyday needs of the community, and has done for over 100 years. If current regeneration proposals go ahead, a unique east end market will be purposefully gentrified beyond recognition, displacing its community and bustling marketplace in the process.

Please note that this film is displayed here for personal viewing only. Commercial or educational screening of this film is unauthorised without prior consent. Please use the Contact button for all enquiries.

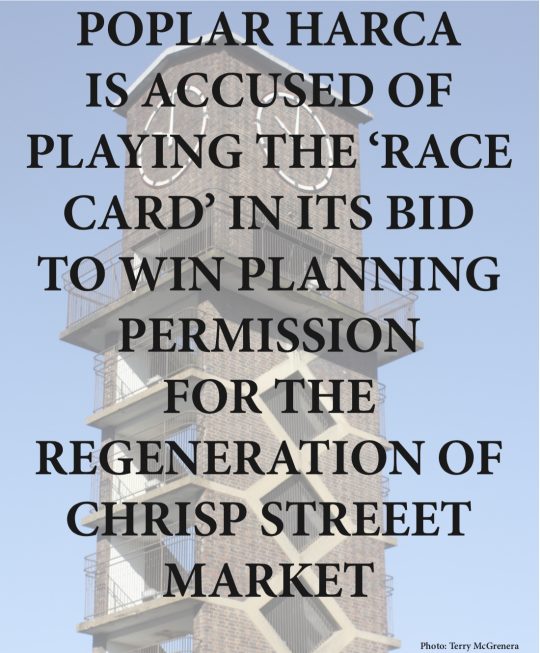

Terry McGrenera investigates the social cleansing of Chrisp Street Market by Poplar Harca and the London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

A Balfron Social Club guest blog post.

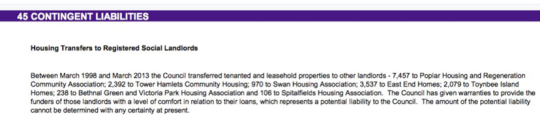

One of the first decisions taken by the New Labour government in 1997 was to establish local housing companies as a symbolic act of how they would embrace new thinking as a means to provide homes. Poplar HARCA, after receiving a loan of £223,100 from Tower Hamlets Council, was one of the first local housing companies. In just over twenty years it has gone from being a community housing provider to a commercial housing provider, predominantly, as is clear from the plans for the redevelopment of Chrisp Street market.

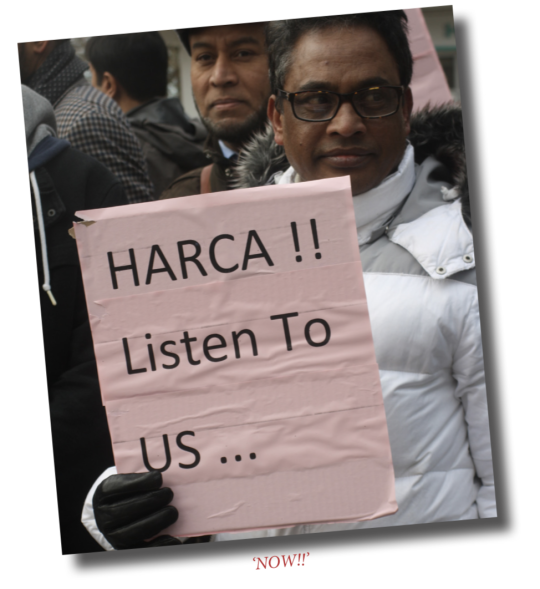

The growing anger at the lack of involvement in the plans for the redevelopment of Chrisp Street market between residents, shopkeepers, market traders and Poplar HARCA was seen by the demonstration outside their head offices last Wednesday. Also shopkeepers are very unhappy with the unacceptable behaviour of one particular person who has been pressurising them to sign new contracts.

Poplar HARCA failed to set up a Chrisp Street market redevelopment committee to engage and involve people. The whole approach has been top-down not bottom-up. It was only when the planning application was published last week that the full extent of what is proposed was learned, despite page 88 of the 100 page application stating that for the past FOUR years there has been “detailed pre-application discussions around layout, heritage assets and intricate design detailing and specifications.” For the past four years there have been NO detailed discussions about such matters as car parking and social housing provided by Poplar HARCA.

Poplar HARCA has been promoting the regeneration of Chrisp Street market by telling people of the number of new homes that would be built. In total there will be 649 new homes. The number of new homes for sale will increase by several hundred percent whilst the increase of new homes to replace the 124 social rented homes demolished will be SEVEN. In the recently completed Watts Grove site build by Tower Hamlets there are 148

homes. There are no studio flats. It is the same for Chrisp Street. Why is Tower Hamlets council failing to include single people – young and old – in its housing plans? Page 98 of the plans states that it complies with the Equalities Act. It doesn’t.

The land where the new homes will be built is used presently by shopkeepers to unload supplies and park their cars. They have been told that space will be provided somewhere off-site. I tried to find ‘the space’ on a large A-Z; I couldn’t.

Car parking is just another example of how the planners have failed to comprehend what Chrisp Street market means to everyone affected by the current plans. That was best expressed by Sr. Christine Frost from SPLASH – South Poplar and Limehouse Action for Social Housing – at the meeting organised by shopkeepers on 10 February at St Matthias church hall attended by 200 people, including the Mayor. Sr. Christine rebutted the loss of retail space and the assumption that people could always travel to Stratford or Canary Wharf to go shopping by saying, “Iceland in Chrisp Street is where people go to shop, not Waitrose (in Canary Wharf).”

The ultimate irony and insult is that although the plans have considered factors such as air quality, biodiversity, contaminated land, flood risk, microclimate, crime prevention, aerial reception and noise impact there is no study on the social impact the plans will have because it is beyond the remit of the planners. In other words, people don’t matter but I think they will come May 3rd. Irrespective of tonight’s vote it will not be the end because on page 69 it states “The current scheme ASSUMES grant funding from the GLA for the reprovision of the social rented units.” Under the new guidelines issued by the Mayor of London that will require a vote of everyone affected by the plans.

• The eight members of the committee rejected the plans by SEVEN votes to ONE.

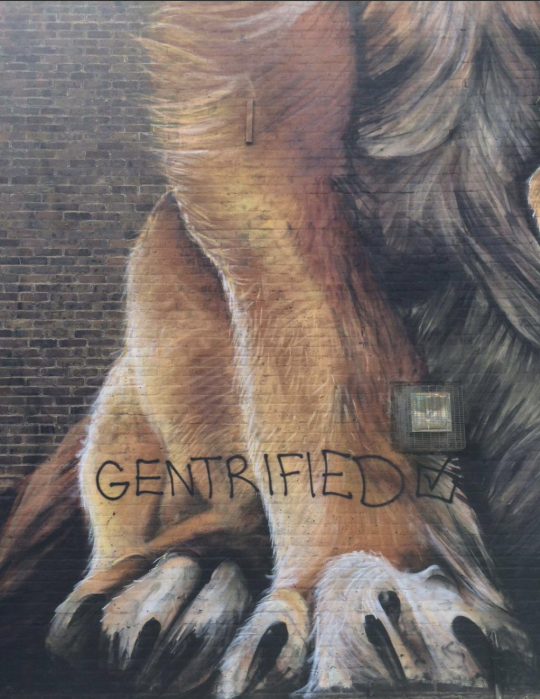

In the week before the vote Poplar HARCA stuck posters about their plans onto pillars in the marketplace. Some people were not amused.

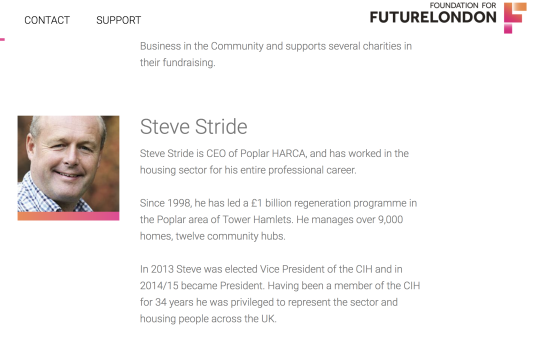

Shortly after the 1997 general election I was walking towards Bow Road tube station when I met Jim Fitzpatrick, the newly elected Labour MP for Limehouse and Poplar, coming out of the station. I had got to know him during the campaign whilst working for a magazine based in Docklands. I was at York Hall on the night he was elected. Anyway he asked me what I knew of a housing organisation called Poplar HARCA. Very little, I said. Over the following twenty years, I and a lot more people were to get to know a lot about Poplar HARCA and the man who was became its chief executive and the way he ran the organisation. He was also to become the chief motivator for the plans to redevelop Chrisp Street market.

President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s in the middle of the greatest economic depression that America had ever known introduced what he called the ‘New Deal’ – a series of initiatives to get young people doing something useful and paying them to do so. On the same day as the initiative became operational an ambitious young man put himself forward for the job of administering the programme in his home state of Texas. His quick thinking and eye for seizing an opportunity saw him become the youngest state director of the programme in the whole of America. He was twenty-seven.

He began to find sponsors to provide the material for the various projects he undertook. One of his first tasks was to find housing for his staff. Within six months he had 18,000 young people working on creating parks and building homes. In doing so he came to the attention of politicians which helped him when he decided to stand for election in later life. John Fitzgerald Kennedy turned to him to help the Democratic Party win Texas and become President. His name was Lyndon Johnson. He became President after John Kennedy was assassinated in 1963.

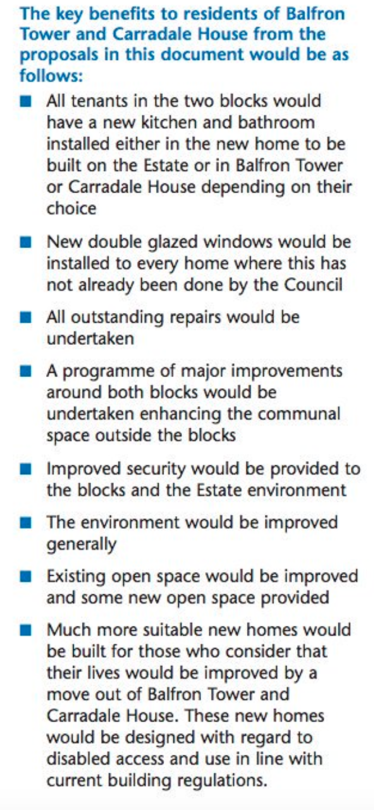

At the time the position of chief executive of Poplar HARCA became available the person who got the job was working for Tower Hamlets council. He applied and got the job. Although he had no political ambitions – he did become President of the Chartered Institute of Housing in 2014 – Poplar HARCA over the next twenty years grew with more than a little help from a very New Labour council along with the backing of a very New Labour government. Labour was reluctant to spend money on housing and adopted a policy of divesting control of local authority housing stock to such local housing companies as Poplar HARCA. Its property portfolio enlarged as thousands of people voted to transfer with the promise of new kitchens and bathrooms. This was Labour’s ‘New Deal’ for housing.

So what has happened to Poplar HARCA over the past decade since the credit crunch? The simple answer is that its fortunes have changed as did the government from Labour to Conservative in 2010. George Osborne in his first comprehensive spending review ended the capital provision for social housing and as a result social housing providers had to seek an alternative and more profitable source of income from building homes – the private market.

Poplar HARCA changed from renovation to regeneration. It reinvented itself; it followed the money. In doing so, as with other social housing providers it strayed somewhat from its original purpose. Symbolic of the change was its change to a Community Benefit Society. It meant registering with the Financial Conduct Authority and changing some of its internal governance processes, as they state, “to ensure smooth business operations.”

What is clear is that business operations for Poplar HARCA weren’t running smooth. In November 2015 it applied for an exemption from the one per cent rent cut after seeing its credit rating downgraded by Moody’s, the credit ratings

agency. The downgrade was issued because the rating agency believed Poplar HARCA would face difficulty making the savings and conversion of large amounts of property to the higher affordable rent level needed to give it viable scope on its covenants. (Poplar HARCA in 2013, through its finance arm Poplar HARCA capital issued a £140 million bond to support future plans).

The Balfron Tower fiasco did little to inspire confidence. Back in 2007 tenants voted to transfer to Poplar HARCA with the promise not only of improvements to the block but tackling a serious anti-social behaviour problem. Tenants were given the option of moving out to new homes or stay whilst the work took place. The credit crunch forced a change of plans. It meant that to recoup the money spent on improvements; Poplar HARCA had to sell Balfron Tower.

Tenants felt betrayed by the failure of Poplar HARCA to keep its promises. This wasn’t the only instance where Poplar HARCA was forced to sell off properties it had inherited from Tower Hamlets Council. In November 2107 it sold off fifty homes which had originally been part of the council’s social housing stock despite an offer from the Mayor to do a deal.

The voracious appetite of Poplar HARCA to do deals first and then work out the details later has come unstuck over the Chrisp Street market plans. The plans as presented to the Strategic Development Committee had so many faults and mistakes which were obvious to anyone with local knowledge. Elementary mistakes such as the car parking site designated in the plans for shopkeepers didn’t exist. The failure to spot such howlers proved that the consultation process was a joke. Furthermore believing that building private flats upon the Co- op car park and expecting the market to survive is perhaps the most pernicious aspect of the plans. Thirdly stating that demolition and building work lasting two years would not significantly impact upon the quality of life of people living around the market is a statement of denial. Fourthly the language used to justify the reduction in retail space is condescending – let people go to Stratford or Canary Wharf. The lack of any confirmed social housing – the reprovision of the social housing which will be demolished is “assumed” upon receiving funds from the Mayor of London. Whoever fiddled the figures on social housing by including shared ownership in the same section should be sacked.

There will be changes in personnel following the failure of Poplar HARCA to obtain planning permission. Whoever approved the plans at Tower Hamlets Council should start packing their cardboard box. At Poplar HARCA it remains to be seen who will carry the can and who will fall on their sword if the plans are to be resurrected for a second coming. The chief executive of the National Housing Federation is retiring in September and a vacancy exists for someone with previous experience at chief executive level of a housing association. Also the question of whether Poplar HARCA remains a separate entity is doubtful considering the number of mergers and acquisitions that have taken place recently.

The survival of Chrisp Street market is occurring almost a century after George Lansbury and Poplar Borough councillors took a stand against proposals to set a rate to pay for the precept on London-wide bodies because of the refusal of the London County Council to equalise the rates London-wide. Their stand became known as ‘Poplarism’. John McDonnell, in the foreword of the book Guilty and Proud of it by Janine Booth about the struggle that ensued, writes, “The Poplar story shows for this generation facing its own periodic crisis of capitalism that people can mobilise and, if determined enough, they can win through.” History is repeating itself.

The present situation as regards the plans to regenerate Chrisp Street market all began with the hopes and dreams of the post-war period. It was a time when, after a second world war in a couple of decades, organisations such as the United Nations were founded to provide a forum where any future disputes and conflicts could be settled by other means than warfare. In the years that followed other organisations were established to improve the health and human rights of people on a global basis. At home it was also a time for the newly elected post-war government to seek new ways to improve the everyday lives so that they could it was hoped achieve their dreams. No better example of such ideals that prevailed at the time was to see that everyone who had lost their homes as a result of the war-time bombing, especially in the East End had somewhere to live. It was the nineteenth century social reformer John Ruskin who said it was the first duty of a state to see that all born there within should be well housed.

As W. Eric Jackson in his history of the London County Council, titled Achievement, of the prevailing line of thought of those times, writes, there was an acceptance that a town must not be a “mere assembly of unrelated parcels of private property, but a composite entity, which owners, occupiers and developers can alter and influence. A well-made planning scheme, properly implemented, can improve both happiness and efficiency and make life more agreeable during work and leisure.”

Such an effort would require a grand plan and in the last year of the war a planning act was passed which enabled the LCC to take drastic measures to deal with blitzed and slum areas by way of comprehensive reconstruction. The LCC obtained authority in respect of an area of 1,312 acres in the Boroughs of Poplar and Stepney to begin the reconstruction. W Eric Jackson writes, “The Festival of Britain, 1951, helped the LCC in its intentions for these areas. Special facilities were granted to the LCC to develop the Lansbury Area in Poplar as an exhibition of ‘live architecture’ with provision for schools, dwellings, shops and open space.”

During the summer of 2017, on Fridays and Saturdays, in Chrisp Street market some young staff members from the Victoria and Albert Museum in their little lock-up rather aptly situated directly beneath the Clock Tower displayed some artefacts from the ‘Live Architecture’ exhibition of 1951 to remind people of the historical context of the estate’s development and the impact of architecture on their lives. The leaflet they distributed described the thinking behind their proposals. It states, “In their aspirations to rebuild London in the aftermath of the Second World War, the architects and planners of the London County Council proposed radical new approaches to making successful communities. Poplar and Stepney were chosen as test beds for the development of 11modern, interconnected neighbourhoods and were planned as self-contained ‘towns’. Though housing was their most pressing concern, this need was not considered in isolation. Each neighbourhood – of which the Lansbury Estate was Number Nine – also included designated areas for parks, industry, churches, roads and rail links as part of one overall design.”

The leaflet adds that Neighbourhood Number Nine was the first of these to be built and was exhibited as a live model of progressive planning ideas as part of the Festival of Britain in 1951. The residents of Lansbury Estate were among the first in London to experience the ideals of post-war social housing; it was to pioneer a modern way of life for a new area.

Unfortunately the idealism of the post-war years and the ‘you’ve never had it so good’ of the 1950s gave way to the decline of the docks in the East End in the 1960s just as the London County Council gave way to the Greater London Council in 1964. The GLC, under Ken Livingstone, was abolished in 1986 as it was seen as a rival source of power to Margaret Thatcher across the River Thames at Westminster.

It was Margaret Thatcher who was also responsible for the transformation of the Docklands east of Tower Bridge. Nobody could have foreseen the metamorphosis that took place under the aegis of the London Docklands Development Corporation since 1981 when it was given complete control of planning in the twenty five years that followed until it was considered to have completed its remit of regenerating the decaying Docklands.

For Rowan Moore, architecture critic of the Observer and author of ‘Slow Burn City: London in the twenty first century’, Canary Wharf, the symbol of the new Docklands is “stupendous, a gigantic thriving place made out of almost nothing in twenty- five years.” He admitted that “It is also the object of criticism at its visible divisiveness, at the impossible-to-miss difference between its prosperous order and the degraded environments outside its boundaries.” Quoting Owen Hatherley, author of ‘A new kind of bleak; journeys through Urban Britain’, “Canary Wharf has been for the last twenty years the most spectacular expression of London’s transformation into a city with levels of inequality that previous generations like to think they’d fought a war to eliminate. Very, very few of the new jobs went to those who had lost their jobs when the Port of London followed the containers to Tilbury; those that did were the most menial – cleaners, baristas and prostitutes. The new housing that emerged, first as a low-rise trickle in the 1980s and 90s followed by a high-rise flood in the 2000s, was, without exception, speculatively built. Inflated prices, dictated by the means of a captive market of bankers, soon forced up rents and mortgages in the surrounding areas, a major cause of London’s current acute housing crisis.”

Hatherley takes issue with the ludicrous nonsense of “trickle- down economics” as represented by Canary Wharf, more so than anywhere else in Europe especially when juxtaposed to the poor state of three architecturally notable nearby council estates. He writes “if anyone in any of these estates has seen anything trickle down it would be an unpleasant-smelling liquid running from a great height.”

Hatherley is not the only critic of what has evolved as a result of the regeneration of Canary Wharf and Docklands. Anna Minton is the author of ‘Ground Control’, a book about the privatisation of former public places in the name of regeneration. She writes that the belief in the ‘trickle-down’ effect justified the new private estates – such as Canary Wharf – which are underpinned by the idea of being very profitable ventures in themselves, pulling in high rents and billing high service charges. There are no pound or charity shops in Canary Wharf. Most important of all, Minton adds, “they promised to transform places by increasing not only their own property values but those in the surrounding area, bringing in so much wealth that it somehow flows out of the gates of the gated properties and ‘trickles down’ to the surrounding poor.”

Anna Minton, after visiting the Isle of Dogs, writes that the area seemed to be on a different planet to the hi-tech, protected enclave that literally towers above residents, “where people really were as ignorant of each other’s habits and way of life as if they were dwellers in different zones. It was also clear that none of the wealth from the neighbouring skyscrapers had found its way on to Millwall’s housing estates or into the pockets of their residents.” The often derelict warehouses lining the riverbanks of the loop of the Isle of Dogs proved an attraction for property developers which added to the sense of resentment felt by residents unable to share the wealth in their midst. In such a diverse borough as Tower Hamlets this inevitably manifested itself at the time in racial tensions over the allocation of council housing to ethnic minorities which was exploited by politicians.

Rowan Moore admits the London Docklands Development Corporation created thousands of jobs with the regeneration of Docklands and mentions that the Canary Wharf group has made contributions to financing affordable housing and public transport in Tower Hamlets as well as the mentoring of young people in the borough. Ultimately Canary Wharf is an emblem of the well-known political dilemma of modern market economics; the dependency on financial institutions whose power exceeds that of elected governments, which contributes to the widening gap between rich and everyone else. Moore ends by mentioning that financial institutions, like Canary Wharf, which in 1992 went bust. Therein lays the problem. The problem as he sees it is a London-wide problem that “regeneration equates to rising property prices equates to gentrification equates to exclusion of people on low or middle incomes.”

The significance of what happened in Docklands as regards the proposed regeneration of Chrisp Street market is that the plans by Poplar HARCA are an attempt for the gentrification that occurred in Docklands to cross the East India Road into what remains of the heartland of the East End. The difference is that the redevelopment of Docklands was largely of a derelict site whereas the Chrisp Street market and the surrounding area

is a residential area and the plans by Poplar HARCA would mean massive disruption to people, businesses and one which would inevitably mean that the market would not survive in the new setting. As a recent report by the London Assembly makes clear of the fifty estate regeneration schemes that have taken place they have resulted in the loss of 8,000 social rented homes whilst the number of private homes has increased tenfold.

When I met the chief executive of Poplar HARCA late last year – at his request – I gave him a copy of Anna Minton’s latest book called ‘Big Capital’. (The title works on two levels; Big Capital refers to the growth of London and to the amount of money that is flowing into London)The book arose, Anna Minton explains, from a conference she attended in 2015 in Bristol about the housing crisis. Speaker after speaker talked about the demolition of London’s housing estates and the devastation caused to communities. As a result she began to specifically research this aspect of the housing crisis. Somewhat strangely it was the financial crash of 2008, aided and abetted by quantitative easing, which added another dimension to the housing crisis. It allowed people with access to funds to invest in property whilst the rest of the population struggled to keep a roof over their heads. The imposition of an austerity policy by the government in the name of financial responsibility acerbated an already dire situation.

Anna Minton’s book makes explicit links between the sheer wealth at the top and the housing crisis, which does not just affect those at the bottom but the majority of Londoners who struggle to buy properties and pay extortionate rents. From the removal from their homes of people on low incomes to the use of property purely as profit and no longer as a social good, the active flouting of democracy by business and local councils. This, Minton defines, is the new politics of space which is replacing the politics of class.

Minton makes clear also that what is happening isn’t gentrification as defined by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe the changes that were taking place in Islington when middle-class people moved into old working-class homes. Glass wrote about the trend thus, “One by one, many of the working class quarters of London have been invaded by the middle classes. Once this process of ‘gentrification’ starts in a district, it goes on rapidly until all or most of most of the original working class occupiers are displaced, and the whole social character of the district is changed.” Commenting on what happened Minton writes that at least the 1960s version of ‘gentrification’ had the positive effect of improving an area but what is happening today is totally different.

Anna Minton, now a lecturer at the University of East London in Docklands, writes, “(But) the speed of capital (that) flows into places between the 1960s and the early 2000s bears no comparison to what is happening today. The rate of return on London property, even in a market slowed by economic uncertainly far exceeds growth, let alone wages, which are among the lowest in Europe. It is these rates of return on property that are driving the reconfiguration of London, boosted by policy decisions carried out by local authorities, which are in tune with deliberate changes in housing policy and the property market, designed to take maximum advantage of the attraction of London real estate to global investors.” It is not just global investors but as the organisation Transparency International, which monitors the movement of money into tax havens around the world, commented in its report Paradise Lost in 2016 “The UK is a prime destination for corrupt individuals looking to invest or launder the proceeds of their illicit wealth, enjoy luxury lifestyle and cleanse their reputations.” (The publication of the Panama Papers showed that London is the world capital for corruption and money laundering, the proceeds being channelled directly into luxury property purchases.)

As a result, Minton writes, “London and many other British cities no longer serve people from a wide range of communities and income brackets, excluding them from expensive amenities and reasonably priced housing and forcing them into intolerable conditions or out of the city altogether. London is an acute example of why this is happening. Today, capital flowing (in) to every aspect of land, property and housing means the whole system has opened itself up to financialisation. From the market in student housing to ‘super prime’ properties, the result is a system failing to meet the needs of people.” Therefore Anna Minton asks the simple question, ‘Who is London for?’ When I gave the chief executive of Poplar HARCA a copy of Anna’s book I hoped he would take heed of the contents and that his plans for Chrisp Street market would not feature in any future edition of the book. It would seem it was too much to expect.

Poplar HARCA and its chief executive have come a long way in a relatively short period of time. It was barely more than a month after the general election of 1997 that Tower Hamlets council’s Housing Services Committee on 11 June met to consider a report from the Corporate Director of Housing regarding the proposed constitution of Poplar HARCA. Its constitution would take the form of a Memorandum and Articles of Association and proposed to be a charitable company limited by guarantee. In the light of what has happened over the past twenty years and the plans for Chrisp Street market it is hard not to laugh when the Memorandum of Association states the objects of the Memorandum of Association are that “The HARCA will have very wide charitable aims. The primary object will be that of providing housing to people who satisfy the charitable tests of poverty, age or disability.” Charity began at home for some members of staff. As to who was a proper beneficiary of charity it did not address in detail. On 30 July 1997 the Finance Committee considered a report to make a loan by way of grant to Poplar HARCA of £223,100 to cover the salary set up costs for a senior management team from September 1997 to the date of the first housing stock transfers.

In the years that followed there were a number of proposals put to council tenants to transfer from council control to Poplar HARCA. In almost all instances where there was a ballot to transfer there was a battle between rival groups of tenants for and against the decision the process to change landlords. Supporters of Poplar HARCA told tenants they would have their homes brought up to the Decent Homes Standard that the government had introduced and that they would involved in decision affecting the estate on which they lived. They were opposed by people who argued that tenants were being forced to choose between improvements to their homes or being ‘left to rot’ should they vote against transfer to Poplar HARCA.

Both groups believed in the righteousness of their beliefs. People against transfer regarded those in favour of transfer as ‘stooges’ swayed by the prospect of become a board member of the new body.

It was an unfair fight as transferring council estates to outfits like Poplar HARCA had the backing of the very New Labour Tower Hamlets council. Besides the promises made about participation in decisions and putting tenants on estate boards, Poplar HARCA saw fit to engage in activities which became their trademark as shopkeepers in Chrisp Street market became all too familiar recently.

In 1998 following the vote to transfer to Poplar HARCA on six estates, including Aberfeldy, Lansbury West and Teviot, supporters against the move brought their concerns about the tactics used by Poplar HARCA to the attention of Tower Hamlets Council. In a ten-page submission to Tower Hamlets Council they accused officers of being less than truthful about the real implications (privatisation) of transferring and that it was their aim to achieve a ‘yes’ vote to transfer by whatever means available. Under five headings they described their concerns about the consultation process prior to the vote. The most serious of their concerns was the use of bribery to encourage people to attend meetings hosted by Poplar HARCA. (Offering tenants £10 to come to a meeting which they were told not to repeat) First on their list of concerns was coercion by means of undue influence placed on tenants to vote for transfer to telling them they would be given new homes following the transfer. Ballot papers were also delivered and collected by hand.

Stephen Beckett, a Labour councillor for East India Ward at the time, even before the ballot took place wrote an open letter stating that he would be resigning from the board of Poplar HARCA due to concerns about the consultation process. In his letter, 13 April 1998, he wrote, “I do not believe that the consultation exercise has been completely genuine. I can only describe the consultation process as a massive propaganda exercise to obtain a ‘yes’ vote.”

After consolidating their hold on considerable swathes of property and homes in the area Poplar HARCA entered into talks with Tower Hamlets Council about the regeneration of Chrisp Street and the Lansbury area. Its redevelopment seen, in time to come, as a testimony to his time as chief executive of Poplar HARCA in the same way as the area is named after the former leader of the Labour Party, of which he has been a member since adulthood. To that end a report by the Corporate Director of Development and Renewal came before a meeting of the Cabinet on 9 February 2011. This was after talks, which began in October 2009, and in January 2010 considered two proposals for evaluation. One was for refurbishment and the second involved a far higher level of demolition and new building. The report states that the scheme proposes 100,000 square feet of retail space and 50,000 office or community space. It was proposed to increase the number of private homes by 480 (from 83) and affordable homes would rise from 150 to 287. The Chief Financial Officer commented that “The proposal involves the disposal of Council owned land to Poplar HARCA in order that the redevelopment scheme is viable.”

The plans for the redevelopment of Chrisp Street market continued apace to the extent that by June 2014 the chief executive of Poplar HARCA felt sufficiently confident to take the deputy editor of Inside Housing magazine, Nick Duxbury, on a tour of the market. It was the week before the Chartered Institute of Housing’s annual conference which the chief executive of Poplar HARCA had been elected to serve as president for the following year. Not bad, as he relates in the article, for someone who began as a housing trainee at Southwark Council. It is fair to say that he has fought his way to the top and been unafraid to resort to methods of persuasion not part of the curriculum at any charm school. (On the day of the ballot for Lansbury Estate held at Trussler Hall, a community hall subsequently given to Poplar HARCA, he came outside and harangued some Defend Council Housing supporters who had the audacity to hand out leaflets to people going inside to vote).

As is the case of a lot of people who have made their way to the top by their own efforts, they tend to discard some aspects of their earlier persona and have some of their rougher edges smoothed off as befitting their present position. That could said to be true of the chief executive of Poplar HARCA. They are in a position to hire people to perform such tasks that they consider unbecoming of their status. It is also possible that the enormity of a task involving contract negotiations required called for a company that specialised in such matters. Poplar HARCA hired AMM Ltd.

As Shoruf Uddin from Photogenesis, a shopkeeper who has traded in Chrisp Street market for nearly twenty years at the meeting held at St Matthias church hall on 10 February, said that although he became aware of plans to regenerate the market in 2016 it was only recently that the reality of the plans came to light when market traders and shopkeepers organised a joint meeting to discuss the situation that the full implications of the plans dawned on them. (Poplar HARCA’s agent asked market traders to approve the plans without explaining them in detail. The plans were first exhibited at the Idea Store in Chrisp Street on 14 January 2016. They was viewed by less than 30 people).

Approaching stakeholders individually rather than collectively seemed to have been a deliberate ploy by Poplar HARCA’s agents. It seems also a deliberate ploy to put none of the promises in writing including a written agreement or confirmation of continuing to hold a commercial lease and tenancy. This allowed people employed by Poplar HARCA to make different promises to different people, in particular what sites they would be allocated in the new layout. When shopkeepers started talking to each other they discovered that several of them had been promised the same site! Shoruf Uddin, along with many shopkeepers, were worried about the removal of their current parking facilities at the rear of their shops. They have been told that off-site car parking will be provided in Hind Street, which is at least ten minutes from their premises. That is totally unacceptable. (There is no Hind Street listed in the latest London A-Z, there is a Hind Grove) Businesses are just as concerned about the removal of the Coop customer car park. In the plans it is going to be the site of a high rise residential development.

It was only a week prior to Poplar HARCA’s planning application came before the Strategic Development Committee that Poplar HARCA responded in writing to the tenants of the 31 lock-up units which were due to be demolished and

whether there would be a place for them in the plans. Was it just a coincidence that it was the same day as the shopkeepers held a demonstration outside Poplar HARCA’s head offices in East India Road? It begins, “It has been brought to my attention that you have some concerns with regard to the planning application for the regeneration of Chrisp Street” The letter gives three guarantees to reassure them of their future is factored into the plans for the market and its success. The letter itself purports to come from the chief executive of Poplar HARCA but the space where his signature should be is blank. As traders and shopkeepers held their ‘demo’ a couple of Poplar HARCA staff on the periphery of the gathering handed out flyers to passers-by. It was a sign of their desperation and an indication that the meeting the following week wasn’t going to be the walk-over that Poplar HARCA hoped it would be by making, as one person at the meeting at St Matthias put it, “promises, rainbows and the world.” It was a sign that Poplar HARCA was beginning to lose control of their bodily functions before the meeting on 15 February 2018.

A week before the Strategic Development Committee on 15 February the agenda for the meeting was published by Tower Hamlets Council on their website. The planning application for Chrisp Street market was 102 pages in total. In the executive summary it states that Tower Hamlets Council has considered the particular circumstances of the application against its own borough-wide development plan as well as the London Plan and the National Planning Policy, plus other relevant supplementary planning documents. The summary then proceeds to mention the “comprehensive redevelopment of the site including the demolition of existing buildings and the erection of 19 new builds ranging from three to 25 storeys providing 649 residential units.”

The application was considered to be acceptable in terms of its impact on local views and heritage assets, height, scale, landscaping and had been designed in accordance with Secure by Design principles. The planners were satisfied that the proposal would not significantly adversely impact the amenity of residents in surrounding buildings and would therefore afford future residents of the buildings a suitable level of amenity. Therefore, it states, the proposed development can be seen to be in accordance with relevant development policy and thus acceptable in amenity terms. Furthermore, addition sub- headings include how the proposal would not have an adverse impact upon the local highway or public transport network and would provide suitable.

A strategy for minimising carbon dioxide emissions is in compliance with the London Plan thus making the proposal acceptable in energy and sustainability terms. Likewise the proposed refuse strategy for the site has been designed to accord with the council’s waste management policy. Other factors for which the proposal is considered acceptable include air quality, biodiversity, flood risk, television and radio reception and its impact upon trees.

Yet NOWHERE in the summary is the impact the work would have on the businesses during the demolition and construction period. Failure to include any mention of how businesses would manage to cope during the work is an indication of the lack of thought that has been given to their plight and the contribution they make to the market. It was included in the list of reasons why shopkeepers were against the plans as they feared that they would suffer substantial losses during the demolition and reconstruction phase. Just as the application has failed to acknowledge any negative impact when work begins HARCA’s agents also make a claim that is largely unfounded. AMM’s website claims to have the “support of most existing businesses and traders to the planning application.” Thus the summary concludes that, subject to any direction by the Mayor of London, planning permission should be approved.

Whilst a redevelopment is considered first of all by the planning department other factors have to taken into consideration and these come under the heading of both internal and external responses. What is obvious from the responses is that most of them bend over backwards not to say anything negative about the plans because of what they consider to be the overall planning gain. The loss of mature trees is one example where planning gain overrides other factors. This is true as regards the proposal for the Chrisp Street development.

This is not the first time that mature trees have come under attack. Last year the council axed fifty trees on some open space in order to pave the way for a planning application for a housing development. The site, near Regent’s Canal in Limehouse, as with many open space sites in the borough had been neglected by Tower Hamlets thus making its retention as an open space less sustainable. Subsequently a planning application was submitted to the planning department to build a tower block on the site. This example is testimony to the extent that officers will go to seek compliance – a practice known as second guessing – with the election promises of those in power. In this case it was the Mayor of Tower Hamlets election promise to build 1,000 council homes, presumably before this May’s local elections. Three times the proposal came before the Development Committee and three times it was rejected. Planning officers considered that the proposal should be granted planning permission as the minutes of the November meeting state that in planning terms the benefits of social housing would outweigh loss of open space. Tower Hamlets cannot keep losing open space – and trees – just to increase the chances of a politician of getting re-elected.

A couple of weeks after the Strategic Development Committee meeting on 1 March the Mayor was pictured in the East London Advertiser on a building site to announce, as the headline stated, “Construction work on first of 1,000 new social homes for borough”. (The photo opportunity must have been arranged just after the Strategic Development Committee meeting) The article added that the 33 homes being built in Rhodeswell Road at the Locksley Estate will be ready in two years. As a consolation prize it wasn’t much in comparison to the coverage there would have been had the planning application for Chrisp Street market been approved. Who knows a special issue of the Council’s Our East End would have been rushed out with the Mayor on the front page with the chief executive of Poplar HARCA and a double page spread inside before the election embargo, due to the local elections in May, on such patently political publicity material would have been legally verboten. (Stop press: with immaculate timing the latest issue of Our East End was delivered to the door of every resident in the borough just before the election embargo. Pictured on the front cover is the Mayor under a hard hat visiting the Locksley Estate to publicise the good news or was it a pre-election photo opportunity? Every little helps as one supermarket might put it. Dig beneath the soil and you will find that John Biggs is just a tribal politician.)

A break-down of the space allocated in the plans for the market show that there will be a reduction in the amount of retail space and an increase in other more commercial outlets in the hope that the market will attract a more diverse customer. In theory this is a sound way to proceed. The way it is presented in the planning application shows the dichotomy – cultural divide – that exists between planners and people. The justification for the reduction in explained a very ancien regime way; it states “This reduction in retail space is offset by the centre’s proximity to Canary Wharf and Stratford as key retail destinations and the overall increase in commercial space.” It is reminiscent of Marie Antoinette’s alleged response on the failure of the harvest – “Let them eat cake”. The response that Sister Christine Frost gave to the suggestion that people should travel to Stratford or Canary Wharf to do their shopping epitomises that gap. At the meeting in St Matthias she said, “Iceland in Chrisp Street is where people go to shop, not Waitrose”.

An essential part of any development is the consultation undertaken beforehand to gauge the public response to any proposal. For the private sector it can be a very sophisticated endeavour. Unfortunately, for local authorities, public consultation is still very superficial, perfunctory and even prehistoric. Public notices in some instances are still tied to lampposts with pieces of string. There are no public notice boards in the whole of Tower Hamlets. Whilst not wishing to denigrate the several attempts made By Poplar HARCA to engage the general public the level of response mentioned in the planning application are derisory and pathetic considering the total cost of the redevelopment is around £300 million. Tower Hamlets council notified a total of 1857 properties surrounding the market. In total, 43 representations were returned; 22 in support and 21 against the plans.

It is clear even from the public consultation that took place the plans have almost totally ignored the top two items listed in the application – affordable housing and car parking. Furthermore, to achieve what they consider an “acceptable” level of “affordable” housing the planning officer who wrote the report cheated – yes cheated – by including shared ownership in the “affordable housing” provision section. With the shared ownership proportion removed from the affordable housing section the plans FAIL to meet the borough own requirement as regards affordable housing.

Plus, there is a rider to what is proposed. The applicant’s viability report concluded that any increase in the amount of affordable housing would be unsustainable. It should also be noted that “The current scheme assumes grant funding from the GLA for the reprovision of the social rented units and the intermediate units from the council for the 38 affordable housing units” There is a rider to the rider regarding the amount of social housing. There will be a mechanism which permits an early stage review of the viability report in the event that the construction work hadn’t sufficiently progressed within two years. In plain layman’s terms it is a get-out clause for the developer as regards the promise to provide social housing. Despite this the planning report concludes the section on affordable housing thus, “the proposed development would secure the maximum viable amount of affordable housing. As such, the scheme complies with the relevant policy (of the council) and is acceptable in terms of affordable housing.”

Again the gap between what is the Council’s current preferred mix and reality is startling, alarming and totally inequitable. The table for the breakdown of the proposed housing mix makes the inequitable nature of the breakdown totally clear. After the severe winter weather which has highlighted the plight of the homeless in our midst the reason why so many people are homeless is obvious from the table. Local authorities, particularly Tower Hamlets, are not building the type of housing that would be ideal for them. The total number of homes that were proposed was 649. They range from one-bedroom to four-bedroom. As regards the number of studio flats whether they are social/affordable, intermediate or for sale is zero, zero and zero. Even apart from studio flats being ideal for homeless people, they would be perfect for single people bearing in mind that they constitute two-thirds of all new households in London. Tower Hamlets proposed to salve its conscience by setting aside 66 homes for wheelchair access.

This is not the only instance where Tower Hamlets recently has failed to consider providing any homes suitable for single or homeless people. In the summer of 2107 the Watts Grove development was completed. The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, was present to mark the occasion by cutting a cake and visiting some of the new tenants in their homes. There are 148 homes on the site of the council’s former refuse depot. As with the planning application for the Chrisp Street market, provision was made for large families with the building of a number of town houses. Also a number of homes have been specially adapted to facilitate wheelchair access. What it has in common with the Chrisp Street market proposals is that no provision was included for studio flats. Considering there is a bedsitter block of flats, in Devons Road, across the road from Watts Grove, which has twice been due for demolition, it would have been no great effort to decant the flats and transfer tenants to Watts Grove. Such a leap of imagination was, it seems, beyond the capacity of Tower Hamlets Council and Tower Hamlets Homes. The low rise decanted block, beside the road, with bus stops on either side, would have been ideal for building more homes than the twenty four that presently exist.

Making people use their cars less is, like the poll tax a good idea in theory, but in practice causes problems that are out of proportion to the benefits especially for people who rely on them for their jobs. In addition to the loss of car parking for shopkeepers adjacent to their premises, for customers the loss of the ‘Co-op’ car park will cause massive inconvenience as it has been sold to Poplar HARCA. They propose to build a high- rise building with homes for private sale. The report justifies the loss of the ‘Co-op’ car park by stating that the site (Chrisp Street market) has a good public transport accessibility location and besides, “there are no policies to protect car parks”. (Poplar HARCA conducted a survey which showed that people who used the car to travel to the market was in single figures. Their figures are disputed by traders and shopkeepers.) Losing the car park will be fatal to the future of the market.

The council should be wary of trying to strictly to implementing ‘car free’ developments after the recent fall- out from the Watts Grove site which combined a lack of communications between departments, stupidity – allocating homes to people knowing they had a car – and adherence to policies that are not fit for purpose in some instances, like Chrisp Street market. (Tenants in the Watts Grove development were enraged to discover that Tower Hamlets Council – three months after they moved into new homes – proposed to paint DOUBLE yellow lines surrounding the site. They expressed their anger to the Mayor and the head of parking at a recent meeting). One of the reasons for the success of Canary Wharf is that it provides car parking for both customers and workers.

Come the night of the Strategic Development Committee meeting the reception area of the town hall in Mulberry Place was packed with supporters from both sides. When they were admitted to the public gallery, the Poplar HARCA ‘posse’, as they arrived first, (some by minibus) occupied all of the front seats. The shopkeepers and market traders filled the rest of the seats. It was only when they were in the public gallery that both sides produced placards from under their coats, strictly against protocol. The meeting began at seven and ended after ten. Apart from the opening ten minutes, during which Sainsbury’s planning application for a new development in Whitechapel, was rejected – for a third time – the meeting discussed the planning application for Chrisp Street market for the rest of the time.

Ammar Hasinie, a shopkeeper in the market since 2004, began by stating his objection to the plans by telling of his trials and tribulations with Poplar HARCA during that period. He mentioned Poplar HARCA’s poor repair record. His shop was inundated with water from the flats above his shop. He answered a number of questions from councillors. Putting the case for the redevelopment was Jean Palmer, who owns a jewellery shop. She said, “The market is trapped in the 1980s – dirty, sad, and run-down with its drug-users, beggars and no security. Don’t let the area become a ghetto.”

Then it was the turn of the planning department to explain their decision to grant planning permission to the proposal. This took around twenty minutes. Kate Harrison, the officer presenting the report, and her colleagues then faced questions from the eight members of the committee. They had visited the market the previous week to familiarise themselves with the situation. As a result they raised some aspects of the proposed redevelopment that had thereto not been generally unknown to many people. The future of the Post Office during the construction work was the most concerning. In reply it was stated by a planning officer that there was a possibility that the Post Office would be closed for two years for the duration of the redevelopment. Cllr. Islam was worried about the increase in drinking establishments would create a problem where none exists. Also the police station was included in the buildings to be demolished. Although a proviso in the report stated that should the police wish to maintain a presence on site, that was a matter dependant upon money becoming available to “reprovide the (current) space” in the market.

Serious doubts were now beginning to be seen in the case for approving the application; they grew when Cllr. David Edgar, chairman of the committee, asked about the viability of the scheme in relation to the grant from the GLA in order to replace the social housing units that would be demolished. He did so following the decision of the Mayor of London to seek ballots of residents on estates that are in receipt of funds allocated by him. (The latest amendments to the Town and Country Planning regulations on local plans state that from 15 January 2018 all local planning authorities have to review local development documents including the statement of community involvement.) Alison Thomas, acting service head, Strategy, Sustainability and Regeneration, replied that if councillors decided to grant planning permission at the meeting she didn’t expect a ballot on this scheme.

Cllr. Peter Golds, leader of the Conservative group, said he had examined the Updated Report to the application and noticed that the number of affordable housing units was reduced by six in an effort to increase the number of four bedroom homes and therefore he told colleagues “We should never consider any reduction in social housing in a borough like Tower Hamlets – this is an appalling insult to the families on our housing waiting list.” He was applauded for his statement. Cllr. Asma Begum gave a couple of reasons why she was minded to defer a decision on the application – the influence the night-time economy would have on the borough’s ability to tackle anti-social behaviour and the uncertainly over the future of the Post Office.

Cllr. David Edgar, summing up, said he was “keen” to defer granting planning permission to the application and that in the time afforded by dong so should be used for further discussions and to receive additional reports. Before moving to a vote he sought legal advice from an officer to make sure that the correct process had been followed. Alison Thomas outlined the consequences if the funds from the GLA were lost. It would mean the affordable housing provision in the scheme would “plummet”. Whilst fully within her remit to state the consequences of deferring the decision there is a fine line that officers must not cross – exerting influence upon a political decision. (At this point she turned to a colleague sitting beside her and mouthed something as a sign of her displeasure after failing to convince councillors to grant planning permission for the proposal).

A vote was taken on the decision to defer the application. It was passed by seven votes to one. Cllr. Danny Hassell voted in support of the scheme. (He will be forever known as the ‘councillor who voted for the Chrisp Street market regeneration plans’) He had sat glumly for the latter part of the discussions with his arms folded saying nothing.

Previously he had voted in favour of granting planning permission at a previous meeting last year about building on open green space near the Regents Canal to help house homeless families. Now he had voted in favour of a scheme that failed to provide more affordable housing than already existed. Reasons for the failure to grant planning permission were given as concerns about the viability of the affordable housing in the scheme, the possible closure of the Post Office and finally the disquiet over the loss of car parking for customers and the impact it would have on the future of the market.

Poplar HARCA supporters left the council chamber in sombre mood, abandoning the placards they had brought with them. By contrast none of the home-made posters held aloft by the shopkeepers and market traders lay strewn around the public gallery. They became souvenirs of a famous victory

against the odds. The market traders and shopkeepers were jubilant at the outcome. It was an outcome that was unlikely only a couple of weeks previously.

Poplar HARCA’s management office in the market was closed the day following the vote as if in mourning for their loss. Their loss was everyone else’s gain. Their proposals were divisive, disruptive and dishonest. It was only in the days that followed that even their promises, lies, bullying and harassment paled into insignificance in their efforts to gain support for their proposals when it was learned that some people in favour of the plans had resorted to baser reasoning. In a final effort to win support for the plans, people hired by Poplar HARCA, went knocking on doors asking residents whether they were in favour of the regeneration of Chrisp Street. Shopkeepers in the market also received a visit from representatives of Poplar HARCA and were encouraged to display a poster saying ‘yes’ in the window of their shops to the plans. In both instances if people were unresponsive to the requests it was intimated that the area would become just like Brick Lane, or as it come to be known Bangla (deshi) town. (The electoral ward for the area is called Spitalfields and Banglatown) This is highly offensive to both Bangladeshi shopkeepers and traders who through their efforts have sought to make a living by providing produce, goods and for Bangladeshi people who come to the market. Without them the market would cease to exist. The same is true of Brick Lane.

Poplar HARCA lost the argument in the council chamber for their plans to regenerate Chrisp Street market. It is now evident they have lost any credibility as regards being involved in any future plans. Their plans showed a total disregard for the lives of people who both use the market and depend on the market for a living. Poplar HARCA were of the belief that getting planning permission was just a formality. Understandable considering the way the planners at Tower Hamlets Council bent over backwards to present the plans in a favourable way. Heads should fall.

Chrisp Street market needs to be regenerated. Sadly the scheme put forward by Poplar HARCA was more about changing the social composition of the area as well as profit. Peter Hall, former professor of Planning and Regeneration at University College London, in the book Regenerating London about the efforts at regeneration in Tower Hamlets, comments, “The Bengali community in Tower Hamlets has a very strong, internal sense of community but it’s a very closed-off community, highly segregated from its neighbours and the rest of London. One would want to suggest that as far as possible you ought to create communities of a different kind, which are not so strongly defined in terms of ethnicity or religion or culture or anything else, (but) that are much more mixed.” Doing so, he ends, will require quite a lot of hard thought. Such thinking was never part of Poplar HARCA’s regeneration plans. Deferral made people think again.

Poplar HARCA’s plans for Chrisp Street Market should be compulsory reading for anyone studying urban regeneration.

Since the beginning of the year, there have been numerous articles in newspapers and on television about the housing crisis in London. Just before Christmas the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan at Blackwall Reach regeneration project, with Canary Wharf in the background, announced his London Plan, in Tower Hamlets. It is to replace the soon to be demolished homes at Robin Hood Gardens, a relic of brutalism architecture. Later he visited the newly completed development of 148 homes at Watts Grove and cut the cake to celebrate the occasion with residents.

Located between Robin Hood Gardens and Watts Grove is Chrisp Street

market. It was built as part of the reconstruction programme just after the Second World War. A model of Chrisp Street market, and Lansbury Estate, of which it was part, became the centrepiece of the Architectural Exhibition in the Festival of Britain in 1951. The architect Frederick Gibberd wanted the market to be the focus of local life. As John Grindrod in his recent book, Concretopia, about the rebuilding of post war Britain, writes, “Walking around Chrisp Street today, it remains a recognisably festival-style development with its classic post- war clock tower.” Unfortunately the plans for its redevelopment, as yet, have failed to receive the public scrutiny that two other London boroughs planning major regeneration projects over the past year.

Over the past year Haringey in north London and Southwark in south London have brought forward major regeneration plans; neither has met the approval of residents. In February 2017 Haringey council proposed to enter into an agreement with the developer Lendlease, an Australian company. Lendlease was the company that was chosen to regenerate the Heygate estate in Southwark. The proposed agreement was one of the most ambitious ever undertaken by a local authority in the UK. The proposal, over a 20 year period, was to build 6,400 homes. The snag was that it would mean the demolition of Northumberland Park and Broadwater Farm council estates as well as the shops used by residents.

A cross-party group of councillors looking at the plans concluded that there not much evidence that such schemes had gone well for other councils and were unsure whether Haringey had obtained the best possible deal. Whilst the council has promised residents they will be able to return to the area there is widespread scepticism that will be the case. An article in the Financial Times in December 2017 stated that although the council and Lendlease said there would be 40 per cent affordable housing, campaigners against the plans point to the Heygate Estate where of the 2,500 homes provided on the redeveloped estate, just 82 have rents set at low-cost social rent levels.

The next stage of Southwark’s regeneration plans is being decided. It involves the demolition of the Elephant and Castle shopping centre and replaced with a new shopping complex, 979 new homes as well as an Arts University. The plans were turned down in January 2018 amid concerns of insufficient social housing and fears the scheme would displace small businesses. Hours before Southwark’s planning committee was due to meet on 30th January to refuse the plans, the developer decided to increase the number the percentage of housing available on social rents from 10 to 36 per cent.

The plans by Poplar HARCA and the developer Telford Homes for Chrisp Street market have been in the pipeline for past four years yet it is only recently that they have entered the consciousness of people who will be affected by what was proposed. This is partly because of the work undertaken by Poplar HARCA on other projects such the completion of the work on the Aberfeldy estate, marketed as the Aberfeldy Village – with a studio flat costing from £314,950 – and the blocks of homes that it is building in conjunction with the developer Telford Homes near Langton Park DLR station. (The same developer for Chrisp Street market) Most people in the borough will be unaware of the plans were to be discussed at the Strategic Development Committee on 15th February. It was thought by some people to be just a formality. But such was the growing anger against the plans that a group of concerned residents, shopkeepers and market traders came together to oppose the plans and lodge objections at the meeting.

Chrisp Street market traders believe that they have been given misleading information about regarding the new development. This may be merely a misunderstanding as the market comes under the authority of Tower Hamlets Council and not Poplar HARCA. At the end of day’s trading many of the stallholders have to transport their goods across the road from the market where they are held in storage. Whether that facility will still be available in the plans for the new Chrisp Street market – if there is one – is uncertain.

Car parking is also a worry for shopkeepers who park their goods vehicles in the car park behind their premises. The plan is that the garages and the car parking facility will be used to build homes leaving the shopkeepers unable to unload supplies at the back of their shops. They have been told that a space will be provided somewhere off-site. The present arrangement is ideal and any move will have an adverse affect upon their businesses.

The whole approach to car parking in Tower Hamlets is one that is increasing becoming a vexed issue not only for market traders and businesses but also for residents. As has been mentioned, the Watts Grove development provides homes for 148 families. A large percentage of the homes were built to accommodate large families. That was the attraction when they submitted their bid. Watts Grove is a car-free site. Many of them are now wandering where, like the shopkeepers, they will be able to park as Tower Hamlets council proposes to introduce double yellow lines in the streets around the site. They have the nerve to call the proposals an “upgrade” – it is a prohibition order. Strangely the same car-free proviso doesn’t seem to apply to similar private developments.

The Chrisp Street market development includes plans to build 649 homes yet the disparity of the number of numbers that will be built for the private and the public sector is startling. The number of homes for sale is around 400 whilst the number of social rented homes is increased by only SEVEN. Also there were no studio homes in the Watts Grove development and it is the same for the Chrisp Street market development. Considering that one estimate found that new households of single people increased of 66 per cent in London many people will be asking why isn’t Tower Hamlets building homes for them.

Shopkeepers and market traders were unhappy about the arrogant attitude that Poplar HARCA and its agents tried to force them to agree to the new contracts on their premises. They were worried about the rent, service charges and the amended leases on their premises. One shopkeeper recently underwent a quadruple bypass heart operation. In addition several of the larger shopkeepers are perplexed about the purpose of telling them that they will occupy the same space in the plans. Is it just Poplar HARCA up to their old tricks of promised everything to anyone to get them to sign up to new contracts?

As part of the plans a number of homes will be demolished. Leaseholders, from previous regeneration schemes, where homes have been demolished have been unable to stay where they lived as the compensation was insufficient. Tenants of Poplar HARCA will see their homes demolished and they also face the prospect of moving away from Chrisp Street. The remnants of the working-class community that grew up around Chrisp Street market after the war will be dispersed. The hopes for Chrisp Street market in 1951 at its inception will be also demolished.

In the first week of February the leader of Haringey council resigned. Ultimately her decision to do so came from an arrogant refusal to admit that the plans she was proposing were unacceptable and failed to achieve the public support for their implementation. It was same arrogance by Poplar HARCA that was the reason why councillors on the Strategic Development Committee turned down the plans for Chrisp Street market on the 15th February by seven votes to one.

The final irony is that Poplar HARCA was established twenty years ago with a £223,000 loan from Tower Hamlets council to provide an alternative to the top- down bureaucratic way housing was provided by local authorities. It was one of the new local housing companies set up by the Labour government. It sought to involve tenants in its decisions. The plans for Chrisp Street market are a betrayal of those founding ideals. It is of the ultimate importance that a Liaison Framework Group, involving residents, shopkeepers and market traders is established to ensure that the regeneration will not, as many people fear it will, turn into a means whereby existing residents and businesses are removed and Chrisp Street market becomes just another part of the encroaching gentrification of Tower Hamlets.